One of the great themes of Pope Emeritus Benedict’s pontificate was the theme of Christian unity, especially unity between Catholics and Orthodox—an end to the greatest schism in Christianity, dating from 1054 A.D. In his first homily as Pope, on April 20, 2005, he said his “primary” task would be to work tirelessly to unify all followers of Christ. He repeated that pledge May 29, 2005, on his first journey as Pope, to Italy’s Adriatic seaport of Bari—a pilgrimage site for many Russian Orthodox because it was the see of their beloved St. Nicholas—and called on ordinary Catholics to also take up the ecumenical cause. We wish to be among those “ordinary Catholics” who take up that cause.

It occurred to us that it may be helpful to share in a series of blog posts, the history of the ancient church, the Great Schism of 1054 and what the differences are between the Roman and Eastern Orthodox churches. Through our mission work forging relationships with the leaders both in the east and the west and worshiping with our fellow Catholics of both traditions, we have come to the same conclusion as James J. DeBoy, President of the National Conference of Catechetical Leadership, 1991-1993, who wrote in the Foreword for “Light of the East, A Guide to Eastern Catholicism for Western Catholics” by George Appleyard:

I came to realize that we American Roman Catholics have a strong tendency to think that “our way is the best way” and that any other religious tradition, including Eastern Catholic traditions, just aren’t as good. It was a humbling, yet enriching, experience for me to come to the understanding that the Roman Tradition is different from the Eastern Tradition but neither is better than the other. Both of these two traditions offer rich and deep ways of understanding and appreciating the power and presence of God in everyday life. To be fully “Catholic”(which we have all learned means “universal”) we need to have an understanding and experience of both of these traditions.

We begin where it all began, at Pentecost. In the upper chamber in Jerusalem where the twelve apostles upon whom Christ was to establish his Church with a common life based on apostolic teaching, worship and fellowship were huddled in fear and apprehension. Then they encountered the Holy Spirit, the one who stirs the sparks of the Resurrection into the flames of Pentecost, the Advocate that Jesus promised He would send. They were no longer afraid, in fact, they were changed–animated–emboldened to live again, to go out and share the good news of Jesus—“to go therefore and make disciples of all the nations” [Matthew 28:19].

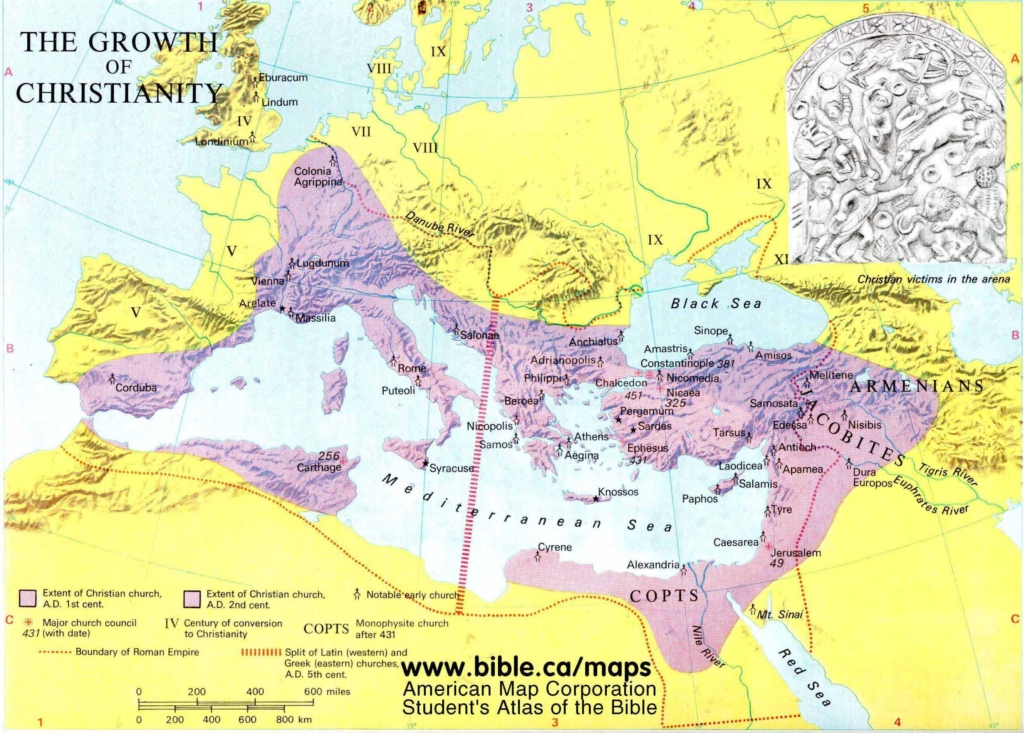

And GO they did! The gospel of Jesus Christ was carried by his apostles beyond the cultural and racial limits of Judaism into the larger world of the Gentiles. As that happened, communities were established and took on the cultural, linguistic, legal and artistic expression of their area. Up until the 5th century, this larger world was mostly the dominant culture of the Greco-Roman world and empire, with the Roman Empire the western most empire of the two great powers west of India, the other being Persia. The Roman world was founded upon the original scattering of Greek cities which the Romans had taken over in their rise to power. (Cross, 1988)

The Greco-Roman World stretched from the borders of Wales in Britain to the town of Dura Europus on the Euphrates and was ruled from Rome by Caesar. It was mostly in Caesar’s world that the apostles preached and ministered Christ. This world was cosmopolitan. Men and women could move about in it without fear of cultural dislocation or disorientation. The dominant languages were commercial Greek, Latin and regional tongues. Alexandria was the most cultivated, artistic and literary center, while Rome was the administrative and political capital until the Empire’s center changed with Byzantium becoming the capital in the 4th century. (Cross, 1988)

The church was cosmopolitan too. It consisted of Christians gathered around their bishops in the towns and cities of the Roman world. There were as yet no Eastern, Western or Oriental churches. Rather, there were great indicative figures among the fathers and writers of the early church who began to bring habits of mind and particular talents and insights, associated with particular regions of the Empire, into the service of the church and of Christ’s truth. (Cross, 1988)

For example, in the West, Tertullian, a North African lawyer, summoned words and concepts from his legal background for use in his theology and this shows in the rather judicial way in which Christians of the West tend to speak of salvation, grace and reconciliation. In the East, Origen was the formative genius of the early church. His exposition of the Scriptures and his defense of the Christian faith led him to forge links between the Christian faith and useful philosophical concepts of the Greeks. His writings that ‘from Jesus began the union of the divine with human nature, so that the human, by communion with the divine, might rise to be divine, not in Jesus alone, but in all who believe and enter upon the life that Jesus taught’ is the basis of the Eastern view of salvation, grace and reconciliation. (Cross, 1988)

Persecution of the early Christians was still rampant and travel was slower keeping some parts of the Empire more isolated; however, these communities did recognize that they were part of a greater, universal Church with one Lord, one Faith, one Baptism. They did communicate with each other, come to each other’s aid in times of difficulty and learned how to enhance their worship and express their Faith from each other. (Appleyard, 2000)

![]()

By the fourth and fifth centuries, St Augustine, bishop of North Africa had produced the first great synthesis of the faith in a Western context responding to the problems and lessons in the experience of West Christians. The same is true of the East. From the painful controversies about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity and the true understanding of Jesus Christ that was begun by Origen and other early fathers, was completed and corrected in the labors of St. Basil, St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Gregory Nazianzus. While clearly there were Western and Eastern churches, they were still the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church and remained in unity for another five or so centuries. (Cross, 1988)

Next in the series… the impact of the conversion of Constantine, the beginning of the Byzantine Church and the centuries leading up to the Great Schism of 1054.

Citations (including links to Amazon to purchase your own copy of these works)

Appleyard, George; “Light of the East, A Guide to Eastern Catholicism for Western Catholics”, Ukranian Catholic Dioces of St. Josaphat in Parma and the National Conference for Catechetical Leadership. Pittsburgh, Pa. Pages iv – xvi; and 1-8.

Cross, Lawrence; “Eastern Christianity, The Byzantine Tradition”, E J Dwyer Pty Ltd, 1988. Philadelphia, Pa. Pages 1-9.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.