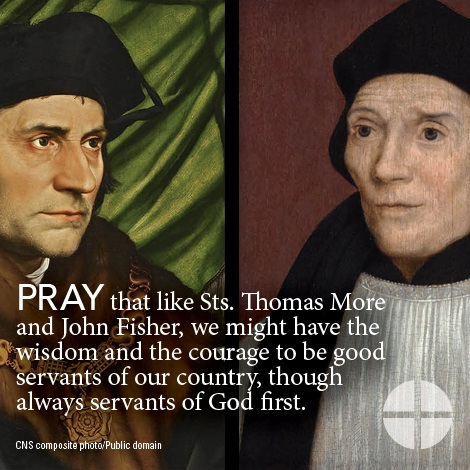

Two more English martyrs who died at Tyburn in 1535 for refusing to acknowledge King Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the Church of England and for upholding the Roman Catholic Church’s doctrine of papal supremacy. They died within two weeks of each other.

St. John Fisher studied at the University of Cambridge (photo, left). He was ordained a priest in 1491 and became the confessor of Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII and served as a tutor for Henry VIII. He ultimately became Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University and worked with Lady Margaret to establish both St. John’s and Christ’s Colleges at Cambridge. Fisher’s strategy was to assemble funds and attract to Cambridge leading scholars from Europe, promoting the study not only of Classical Latin and Greek authors, but Hebrew as well.

St. John Fisher studied at the University of Cambridge (photo, left). He was ordained a priest in 1491 and became the confessor of Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII and served as a tutor for Henry VIII. He ultimately became Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University and worked with Lady Margaret to establish both St. John’s and Christ’s Colleges at Cambridge. Fisher’s strategy was to assemble funds and attract to Cambridge leading scholars from Europe, promoting the study not only of Classical Latin and Greek authors, but Hebrew as well.

Erasmus said of John Fisher: “He is the one man at this time who is incomparable for uprightness of life, for learning and for greatness of soul.”

Fisher has also been attributed as the author of the royal treatise against Martin Luther published in 1521 that gave King Henry VIII the title “Defender of the Faith.” On about 11 February 1526, at the King’s command, he preached a famous sermon against Luther at St. Paul’s Cross, the open-air pulpit outside St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. This was in the wake of numerous other controversial writings; the battle against heterodox teachings increasingly occupied Fisher’s later years.

When Henry tried to divorce Queen Catherine of Aragon, Fisher became the Queen’s chief supporter. As such, he appeared on the Queen’s behalf in the legates’ court, where he startled the audience by the directness of his language and by declaring that, like St. John the Baptist he was ready to die on behalf of the indissolubility of marriage. Henry VIII, upon hearing this, grew so enraged by it that he composed a long Latin address to the legates in answer to the bishop’s speech. Fisher’s copy of this still exists, with his manuscript annotations in the margin which show how little he feared the royal anger. The removal of the cause to Rome brought Fisher’s personal involvement to an end, but the King never forgave him for what he had done.

Fisher was ultimately charged for treason and beheaded on June 22.

He is attributed for saying, “The blessed lady, Mother of our Savior, may well be called a morning, since before her there was none without sin. After her, the most clear sun Christ Jesus showed his light to the world.”

Thomas More was born in London on February 7, 1478. His father, Sir John More, was a lawyer and judge who rose to prominence during the reign of Edward IV. His connections and wealth would help his son, Thomas, rise in station as a young man. Thomas More entered Oxford in 1492, where he would learn Latin, Greek and prepare for his future studies. In 1494, he left Oxford to become a lawyer and he trained in London until 1502 when he was finally approved to begin practice.

By 1504, More had decided to remain in the secular world, and stood for election to Parliament. But he did not forget the pious monks who inspired his practice of the faith. n 1504, More was elected to Parliament to represent the region of Great Yarmouth, and in 1510 rose to represent London. During his service to the people of London, he earned a reputation as being honest and effective. He became a Privy Counselor in 1514.

More also honed his skills as a theologian and a writer. Among his most famous works is “Utopia,” about a fictional, idealistic island society. The work is widely regarded as part satire, part social commentary, part suggestion. Utopia is considered one of the greatest works of the late Renaissance and was widely read during the Enlightenment period. It remains well by scholars read today.

From 1517 on, Henry VIII took a liking to Thomas More, and gave him posts of ever increasing responsibility. In 1521, he was knighted and made Under-Treasurer of the Exchequer. The King’s trust in More grew with time and More was soon made Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, which gave him authority over the northern portion of England on behalf of Henry. More became Lord Chancellor in 1529. During the years of public service of Sir Thomas More, Parliament met in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey. The abbey was later dissolved in 1540 by King Henry VIII.

During our pilgrimage “In the Footsteps of St. Thomas More and Bl. John Henry Newman”, we will have a private tour of the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Hall (photo, left) and enjoy tea with a Member of Parliament. Westminster Hall is where St. Thomas More was tried and condemned under Henry VIII. It is also where Pope Benedict addressed both houses of Parliament during his visit in 2010, the first time a Pope had visited Britain since the Reformation. St. Thomas More’s coat of arms and the “Woolsack” upon which he sat as Lord Chancellor can be found in the House of Commons and the House of Lords, respectively.

During our pilgrimage “In the Footsteps of St. Thomas More and Bl. John Henry Newman”, we will have a private tour of the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Hall (photo, left) and enjoy tea with a Member of Parliament. Westminster Hall is where St. Thomas More was tried and condemned under Henry VIII. It is also where Pope Benedict addressed both houses of Parliament during his visit in 2010, the first time a Pope had visited Britain since the Reformation. St. Thomas More’s coat of arms and the “Woolsack” upon which he sat as Lord Chancellor can be found in the House of Commons and the House of Lords, respectively.

The relationship between More and Henry became strained again when seeking to isolate More, Henry purged many of the clergy who supported the Pope. It became clear to all that Henry was prepared to break away from the Church in Rome, something More knew he could not condone.

In 1532, More found himself unable to work for Henry VIII, whom he felt had lost his way as a Catholic. Faced with the prospect of being compelled to actively support Henry’s schism with the Church, More offered his resignation, citing failing health. Henry accepted it, although he was unhappy with what he viewed as flagging loyalty.

In 1533, More refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boylen, who was now the Queen of England. More instead wrote a letter of congratulations. The letter, as opposed to his direct presence offended Henry greatly. The king viewed More’s absence as an insult to his new queen and an undermining of his authority as head of the church and state.

Henry then had charges trumped up against More, but More’s own integrity protected him. In the first instance, he was accused of accepting bribes, but there was simply no evidence that could be obtained or manufactured. He was then accused of conspiracy against the king, because he allegedly consulted with a nun who prophesied against Henry and his wife, Anne. However, More was able to produce a letter in which he specifically instructed the nun, Elizabeth Barton, not to interfere with politics.

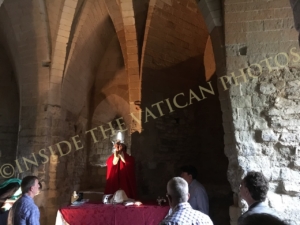

On April 13, 1534, More was ordered to take an oath, acknowledging the legitimacies of Anne’s position as queen, of Henry’s self-granted annulment from Catherine, and the superior position of the King as head of the church. More accepted Henry’s marriage to Anne, but refused to acknowledge Henry as head of the church, or his annulment from Catherine. This led to his arrest and imprisonment. He was locked away in the Tower of London. During our pilgrimage we visit the cell that St. Thomas More was imprisoned (photo, left–and yes we are celebrating mass in his cell, a rare privilege), visit with the nuns at Tyburn Convent and will learn more about his life from one of his descendants.

On April 13, 1534, More was ordered to take an oath, acknowledging the legitimacies of Anne’s position as queen, of Henry’s self-granted annulment from Catherine, and the superior position of the King as head of the church. More accepted Henry’s marriage to Anne, but refused to acknowledge Henry as head of the church, or his annulment from Catherine. This led to his arrest and imprisonment. He was locked away in the Tower of London. During our pilgrimage we visit the cell that St. Thomas More was imprisoned (photo, left–and yes we are celebrating mass in his cell, a rare privilege), visit with the nuns at Tyburn Convent and will learn more about his life from one of his descendants.

He faced trial on July 1. Despite a brilliant defense of himself and persuasive testimony, grounded in truth and fact, More was convicted in fifteen minutes. The court sentenced him to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, which was the traditional punishment for treason.

More ascended the scaffold on July 6, 1535, joking to his executioners to help him up the scaffold, but that he would see himself down. He then made a final statement, proclaiming that he was “the king’s good servant, but God’s first.” He is the patron saint of adopted children lawyers, civil servants, politicians, and difficult marriages.

For more information about the pilgrimage, click this LINK to “In the Footsteps of St Thomas More and Bl. John Henry Newman”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.